AVIVA-Berlin >

Jüdisches Leben

AVIVA-BERLIN.de 7/14/5786 -

Beitrag vom 05.11.2012

A Woman´s Many Names - Dora Sophie Kellner, by Maya Nitis

Maya Nitis

How many names could a Jewish woman have in the Berlin of the 1920´s and 30´s, how many books must she write, translate, how many magazines edit, how many men help, before she might be remembered?

A full biography of Dora Sophie Kellner would undoubtedly present fascinating challenges and surprises. The readily available information about her life is scarce and fragmentary, bits of it appearing in relation to her increasingly legendary second husband of 13 years, Walter Benjamin. The usage of Dora´s middle name is attributed to the need to differentiate between her and Benjamin´s sister, also Dora Benjamin. Changing names at least 3 times, Dora Sophie nonetheless used her own last name – Kellner – for most of her published work that includes translations of novels, journalism, and a novel of her own. Dora S. Kellner inherited her last name from her father, Leon Kellner, a well-known Jewish professor from Vienna, where she was born in 1890. Gershom Scholem, a renowned scholar of Jewish mysticism and a friend of Dora and Walter Benjamin, recounted the influence of "the daughter of a very renown Zionist ´of the first hour´, Professor Leon Kellner, the editor of the oeuvre and diaries of Theodor Herzls" on Benjamin just before their marriage. This close relationship and Dora´s largely out of print, yet traceable published work constitute the remnants from which her life and work can be glimpsed today.

Dora Sophie was not a woman of common morals, hence, at least in this sense, not of her time. A female Jewish writer, working and living out her freedom in Berlin at the beginning of the twentieth century could indeed only be a struggling, if not rare, inhabitant. Dora Sophie pursued relationships (that involved at least 3 marriages, even if the last was due to the political need to flee fascism) with a freedom that surely did not accord with bourgeois norms, and her perseverance in her work, the quality of the work, as well as her understanding marked her as a fascinating and strong thinker and human being. One could say that Kellner managed to focus on being rather than appearance, enabling her to follow her feelings, while being displaced by Nazism and forced to flee across Europe. Her relationships, including marriages, seem to have involved honesty and mutual respect at a radically unstable and non-egalitarian political time. In 1916 "Benjamin visited her frequently at the villa the Pollaks owned in Seehaupt," as she was already separated and waiting for her divorce from Max Pollack.

We might guess that Dora Sophie´s mother, Anna Kellner, also wrote, as translators almost always do: under Dora Sophie´s editorship, which she took over at the end of 1926, die Praktische Berlinerin published a translation by Anna Kellner in 1927. Very little further information appears to be available about Dora Sophie prior to her second marriage to Benjamin in 1917, except her first marriage to the journalist and philosophical pedagogue Max Pollack at the age of 21. Walter Benjamin, a fascinating thinker of "messianic Marxism," continued to play an important part in Dora Sophie´s life through 13 years of marriage, and afterwards, as a co-parent and trusted friend until his death in 1940. Accordingly to Scholem, Benjamin owed to her his second avoidance of military service in 1917, after having been found "fit for light field duties," thanks to an attack of sciatica induced by her use of hypnosis. (1)

The year before her marriage to Benjamin, Dora Sophie reportedly presented him with roses after the 22 year-old Walter´s inaugural speech as Chairman of the Free Students Union. The two met again in Munich, from which they returned to Berlin together and were soon married. If it is true that certain fortuitous details might hide a secret, it is not in vain to mention that on the occasion of their marriage Scholem gave Benjamin a copy of Paul Scheerbart´s Lesabendio (1). Their son Stefan Benjamin was born the following year in 1918. The remaining 11 years of their marriage are shrouded in obscurity, which makes some writers wonder as letter writing was a daily practice and the only real means of keeping in touch in an extremely volatile political situation. The Benjamins had financial difficulties, among others, such as issues of marital loyalty if one is to trust divorce proceedings that so often obscure more than they reveal. It is also reported that while living in Berlin in the early 1920s the pair were already both in love with other people.

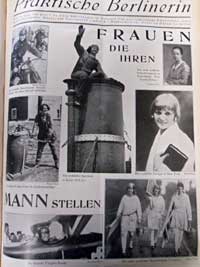

Knowledge of English, acquired from her parents, helped Dora Sophie earn a living. In Berlin Dora S. worked first as a bilingual secretary, and then earned a living by writing short pieces for the German Rundfunk radio (mainly on children´s education), publications such as book reviews for Die literarische Welt, and translations, among them of novels such as the Limestone Tree. At the end of 1926 Dora S. Kellner took over the publication of Die Praktische Berlinerin, a women´s journal that began to publish some interesting material challenging the mores of the time. This is already evident from the first picture adorning the first issue of 1927 – the first one under Kellner´s editorship. On the cover of Die Praktische Berlinerin, a young woman with a boyish haircut and navy blouse is hanging a calendar on the wall with hammer and nail in hand, while her helpers, a small dog and a toddler, rip apart last year´s calendar (see photograph above).

The second issue of 1927 featured photographs of women in "men´s" professions: including the first woman police chief, a firewoman, a pilot and a rabbi (see photo above). In the third issue under Kellner´s leadership, the front cover depicts two people in fancy evening dress, one of them down on one knee before the other: in "gender roles" opposing accepted norms (see photograph bottom of article). The publication generally contained one major article on current events and one piece of fiction, often a novel published in installments, in addition to the notices and fashion advice. In a 1927 issue, the central article appeared entitled: "Wo halten wir? Der heutige Stand der Frauen Bewegung", in English: "Where did we stop? The current situation of the women´s movement"

(see accompanying photo below of an English suffragette, Mrs. Pankhurst, being forcefully carried away by two police officers).

Biographers have underlined the correspondence in Kellner and Benjamin´s life together to the plot of Goethe´s Elective Affinities. Two early visitors nested in their collapsed marriage: in winter of 1921 Dora fell in love with the musician, poet and translator Ernst Schoen while Benjamin received a visit from sculptor Jula Cohn in April of the same year. Between 1923 and 1930 Dora and Benjamin lived as good friends. Scholem reports that Benjamin´s "demon that occasionally possessed him and manifested itself in despotic behavior and claims had completely left him." (2) The end of 1929 and beginning of 1930, however, was not such a happy time in their relationship, since the legal proceedings cut them asunder. Benjamin laments Dora´s "relentless bitterness" in his letters to Scholem at the time.(3) If there might be some (little) doubts about the fairness of the economical verdict during their separation, there are no doubts that Dora Sophie supported the family, in addition to, or, following the financial support of her own and Benjamin´s parents. In the early ´30s their friendship recovered. After all, Benjamin´s character had never been a mystery to her. As early as June 29, 1915, Dora had written to Herbert Blumenthal and Carla Seligson concerning the beloved: "If you love him, then you already know that his words are grand and divine, his thoughts and works significant, his feelings petty and cramped, and his actions of a sort to correspond to all of this." (4)

In 1930, Dora Sophie´s novel Gas gegen Gas appeared serially in the newspaper publication of the Sudwestdeutsche Rundfunkzeitung. This was the same year that Walter Benjamin and Dora S. were divorced. In 1934 Dora moved with her son, Stefan, to San Remo, Italy, where she acquired the hotel Miramare after having worked there as a cook. After their divorce, Walter and Dora wrote to each other, not only as loving parents, but also as considerate, respectful and caring adults until Walter Benjamin´s death in 1940, as their numerous letters housed in the Walter Benjamin Archive in Berlin testify. Walter Benjamin spent some time as a guest at the Miramare in 1934. While most of the letters between them seem to concern primarily practical things, specifically in relation to their son, they are full of brief notes of tenderness. Both Jews, their financial situation is not difficult to imagine after Hitler´s coming to power. Nonetheless, both sent each other what they could when they could, sharing their small gifts and misfortunes from afar. In 1934, Dora Sophie sent Benjamin 20 marks with a note to wish him a nice day and dinner on her birthday, adding that had she had more, she would have sent more.

In 1938, after a political marriage enabling her to go to Britain, Dora Sophie followed her son to London, where she had sent him, fleeing the spread of fascism. She would spend the rest of her life in England, until her death 26 years later in 1964. Little is known of these years, except that in the beginning she continued her work in pensions in London. Until Walter Benjamin´s death, Dora Sophie tried to help him in varying ways, also in his own late attempt to evade the fate that Nazism had imposed on so many... In 1941, writing to Gershom Scholem, she lamented Benjamin´s untimely death as one that would surely but slowly drain away her hopes and dreams for the future.

This fragmentary information about the travails of a Jewish woman in the first half of the twenty-first century Europe, paints a forlorn picture where times and places are barely visible. The changing situation of a life amidst political chaos raises questions about gender, ethnicity, and memory, to name a few elements that stand out in such a partial account. The real story of a loving life spent crossing borders, writing, translating and struggling, remains to be dug out from obscurity, chasing letters and manuscripts obscure or out of print, and, perhaps, also, the dreams others had and lived close to this person whose shadow still wavers on the borders of forgetfulness. Dora Sophie Kellner´s strength and commitment to both her work and those around her presents a fascinating portrait of possibility. One glimpse of which, if not the best, might be given by her comment in 1941 in the same letter to Gershom Scholem, asserting that if she had been with Walter Benjamin before his death, he would not have perished in his flight.

About the author:

I´m an expert ocean hopper, hitching back and forth across the Atlantic. Born in a country and a city that no longer exist - in name and other senses - I first made a crossing as a kid from one state phantasm to another. Bearing a U.S. passport, I criss-crossed the ocean again to the Queer capital of Europe. With a B.A. in English and Political Science, an M.A. in continental Philosophy, currently working on an experimental PhD involving the disjoining of language and violence, I eat words for breakfast (in moments free from teaching languages at two collectives). Present main interests include: translation, queer and critical theory, performativity and flying without leaving the ground (that is, how W. Benjamin described reading, as opposed to copying).

Notes and Sources:

(1) Benjamin, Walter. Selected Writings in 4 Volumes, ´Chronology.´ Ed. Bullock, M. and Jennings, M. Harvard University Press (Cambridge Mass.) 1999-2004; Vol. I, p.501.

(1) 1, 501

(1) Ibid., SW 1, p. 507

(2) Ibid., SW 2, p. 837

(1) Ibid., SW 2, p. 834

See also:

www.adk.de

Das Projekt "Jüdische Frauengeschichte(n) in Berlin - Writing Girls - Journalismus in den Neuen Medien" wurde ermöglich durch eine Kooperation der Stiftung ZURÜCKGEBEN, Stiftung zur Förderung jüdischer Frauen in Kunst und Wissenschaft

und der Stiftung Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft (EVZ)

Weitere Informationen finden Sie unter:

www.stiftung-zurueckgeben.de

www.stiftung-evz.de